About peace

The following text was published as a column in the magazine InZicht, theme issue ‘Peace’

(February 2024 – volume 26-1)

Introduction

“To get free (from your marker), you need technique” Johan Cruyff once said. This applies to many aspects of life, including ‘staying free in peace.’ To remain inwardly at peace in every situation you encounter, we need technique. Technique is developed through practice. In addition to our peace-loving attitude, we need technique to inwardly ‘run free’ and stay that way when faced with opposition or aggression. There are situations where the peace-loving mindset we have embraced is not sufficient to maintain inner peace. It then becomes apparent that we lack the experience gained through practice that allows us to ‘run free.’ We lose our inner peace! If we do not realize this, we continue to react automatically. These reactions are often far from peaceful. If we supposedly ‘peacefully grit our teeth’ in those moments, we drift even further away from peace, as it leads to a loss of connection with others. This results in even more problems of unrest. We ‘lose’ ourselves in situations. It is crucial to become aware of this and to train ourselves in being peaceful, no matter who or what we encounter.

The hope of humanity lies in the transformation of the individual

Jiddu Krishnamurti

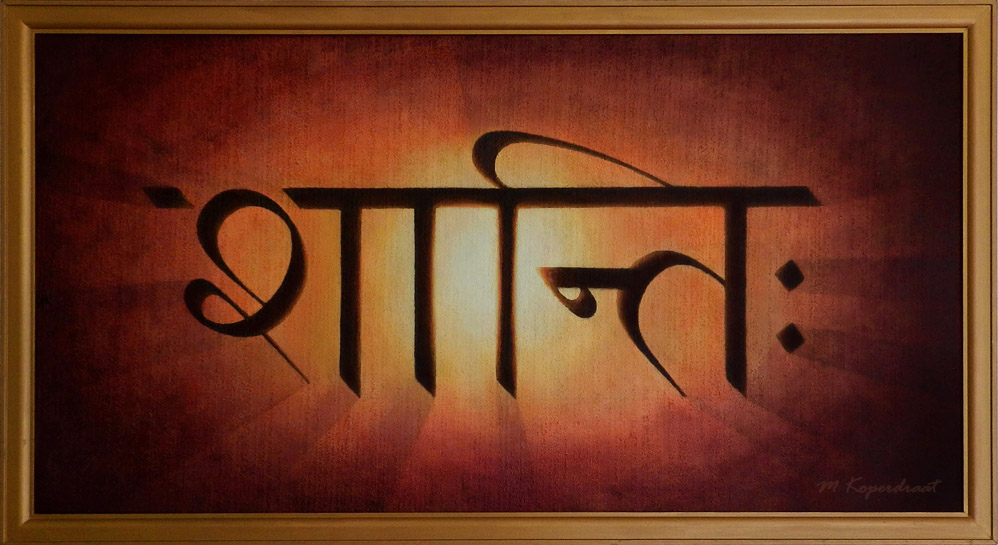

Shanti, shanti, shantih

Shanti, shanti, shantih

In Sanskrit, words often carry extensive and layered meanings. Shanti is Sanskrit for Peace. In both Hinduism and Buddhism, recitations and practices are often concluded with the primal mantra Om, followed by thrice shanti, the last of which is aspirated at the end.

This is officially transcribed as Ōm, śānti, śānti, śāntiḥ. This triad affirms peace of body, mind, and soul and supports us in realizing a more sustainable inner peace, especially when expressed in devotion. Every spiritual tradition focuses on this, for in true peace, there is no duality. The more people realize inner peace, the sooner societal peace can emerge. Our inner path to peace thus paves the way for peace externally.

Shanti (शान्ति) therefore means more than just the peace we know and more than the absence of conflict. Shanti is derived from the root ‘sham’ (शम्), the core from which multiple words emerge about tranquility, harmony, and peace. Sham has many meanings, somewhat akin to the English ‘release’. Sham, supplemented with the suffix ‘ti’, forms the feminine word shanti, with many layers. A visarga may also be added, aspirating the pronunciation at the end. This means that after the vowel ‘i’, you end with a short exhaling ‘h’. This can be symbolically interpreted as exhaling tension, creating space for peace and serenity. In transcription, this is written as ‘ḥ’ and in Sanskrit with a colon (शान्ति:). Transcription indicates with a hyphen above the vowel if its pronunciation should be slightly longer, as seen here with Ōm and śānti, and the emphasis on the ‘s’ makes it ‘sh’.

Shanti affirms positive tranquility and peace on all levels of existence:

- On a physical level, shanti includes health, well-being, and harmony with the material world — and thus with our own body. Nothing is physically harmed.

Affirmation: “I am not my body; it is the vehicle of my soul in this life.” - On the emotional-mental level, it involves an inner calming through which our mind becomes still and stress dissolves. No mental harm is inflicted on ourselves or others.

Affirmation: “I am not my thoughts and feelings; they are my tools for gaining insight and self-realization.” - Socially, shanti implies peace in relationships — the ability to live together peacefully, communicate nonviolently, with understanding and compassion, even when things get difficult.

Affirmation: “I am not separate; I am connected with everyone.” - Shanti naturally implies political peace — locally, regionally, nationally, and internationally — in which every act of war is excluded.

Affirmation: “I support no form of war propaganda.” - Furthermore, shanti implies unity with nature, in peaceful respect for every element within it, because we are inseparably part of it.

Affirmation: “I am part of nature; I honor her — she is the cradle of my existence.” - On a spiritual level, it transcends us as individuals and leads to an experience of connectedness with ‘the world as it is,’ even when it feels difficult.

Affirmation: “I know I cannot be what I can perceive, for I am That which perceives.” - Finally, shanti stands for divine peace: a peace arising from self-realization and union through, with, and in the Divine. It means transcending all duality and experiencing the deepest unity of existence — perceiving oneness behind every diversity and constancy within every change.

Affirmation: “I am the Self that manifests all that is physical (material), subtle (mental), and causal (originating) — both the beautiful and the ugly.”

In summary, repeatedly reciting the mantra ‘Om, shanti, shanti, shantih’ reaffirms our intense desire for peace on all these levels, from the earthly-physical to the highest spiritual. However, it is not enough to stop here. In addition to the intense desire to be ‘at peace’, it is important to lovingly leave behind everything within ourselves that obstructs peace. Unfortunately, we have been taught to identify with many things and thought mechanisms that block natural peace, often without our awareness. In fact, we have even been untaught to remain silent and awake-conscious from our original pure child-being. Assumptions, tendencies, and conditioning acquired through wrong examples or painful experiences (which cause us to experience opposition) can be transcended through practice, through conscious effort in relaxation, in dedicated surrender. Practices exist for the head, heart, and body that connect these aspects, which can be practiced daily and concluded with Om, shanti, shanti, shantih. There is still much inner work to be done, for when we see what people in unconsciousness and in discord do to each other in this world…

In summary, repeatedly reciting the mantra ‘Om, shanti, shanti, shantih’ reaffirms our intense desire for peace on all these levels, from the earthly-physical to the highest spiritual. However, it is not enough to stop here. In addition to the intense desire to be ‘at peace’, it is important to lovingly leave behind everything within ourselves that obstructs peace. Unfortunately, we have been taught to identify with many things and thought mechanisms that block natural peace, often without our awareness. In fact, we have even been untaught to remain silent and awake-conscious from our original pure child-being. Assumptions, tendencies, and conditioning acquired through wrong examples or painful experiences (which cause us to experience opposition) can be transcended through practice, through conscious effort in relaxation, in dedicated surrender. Practices exist for the head, heart, and body that connect these aspects, which can be practiced daily and concluded with Om, shanti, shanti, shantih. There is still much inner work to be done, for when we see what people in unconsciousness and in discord do to each other in this world…

In Indian music, the bass tabla (the bayan) can depict this Shanti triad by striking a bass note thrice at the end of a piece. The magnificent tabla player from the orchestra that accompanied Amma (Mata Amritananda Mayi) during her tours consistently concluded each bhajan in this manner. In Indian classical music, several rhythmic patterns have spiritual significance. The three bayan strikes thus symbolize harmony, peace, and silence (both for performer and listener), much like the words shanti, shanti, shantih do at the end of actions and recitations. They affirm the holy trinity in everything.

Ōm, śānti, śānti, śāntiḥ